I can’t think of a lot of novels that you can put down for 10 years, pick right back up to read the final passages, and then burst out in tears like you just consumed the whole vital work for the first life-saving time. But that’s the power of not one work by the great German/Swiss writer Hermann Hesse, but at least two that I know of: Siddhartha and Steppenwolf.

“I can’t think of a lot of novels that you can put down for 10 years, pick right back up to read the final passages, and then burst out in tears like you just consumed the whole vital work for the first life-saving time. But that’s the power of not one work by the great German/Swiss writer Hermann Hesse, but at least two that I know of: Siddhartha and Steppenwolf.”

I rediscovered these vital pages just this week, whilst trying to think about what to write about for this here arts column. No new movies, shows, or albums really have me all that jazzed at the moment, and I do my best to only be stoked about the stuff I’m sharing here. So, as I do when I’m wandering and restless and not sure, I perused my book shelves. As soon as my eyes stuck on the “used/saved” sticker from my university bookstore (lifelong thanks to Prof. Markman), I knew I had to write about Steppenwolf, Hesse’s tenth novel, originally published in 1927 in Germany, and far more than just a dope band name. It tells the tale of pathetic recluse Harry Haller, who’s too smart for his own good, paralyzed by his rational, bourgeois upbringing, and in constant conflict with his more wolf-like nature, the madman within. The surreal ending inside the “for madmen only” Magic Theater unfolds into a cathartic moment that every possibly crazy artist must read.

But it’s impossible to bring up that seminal work without bringing up Hesse’ ninth novel, Siddhartha, published in 1922 in Germany, brought to our language in 1951, and evolved into a full-on hippie manifesto by the ‘60s. It tells the story of a young man named Siddhartha, who in his quest for self-discovery, may just become everyone and everything. It’s far more grounded than that, as far as the simple tale unfolds, but at the end, you realize that Siddhartha’s not the only one connected to The All.

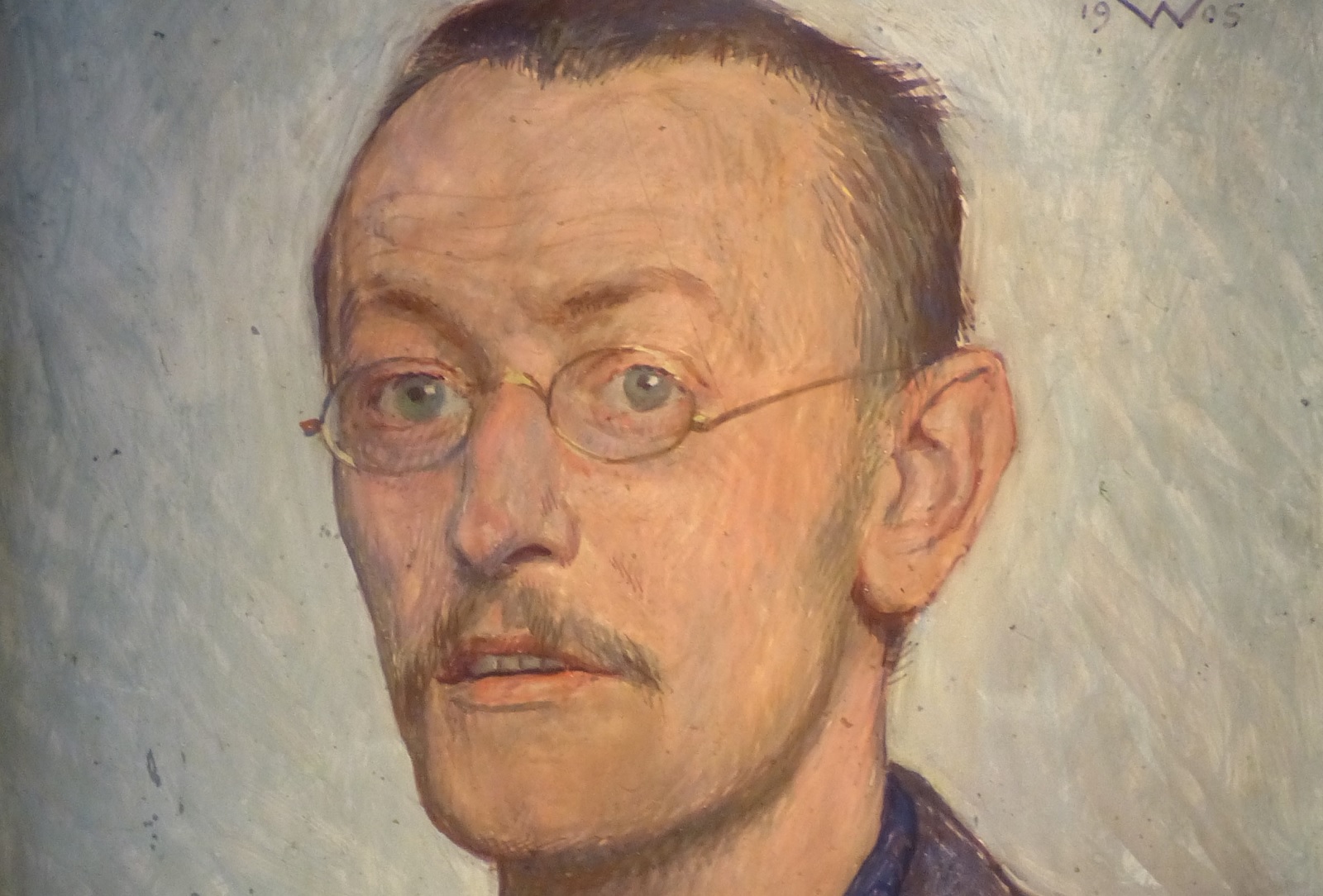

But we’re ahead of ourselves here. Discuss either book without first discussing the man himself would be unwise. Hesse was the ultimate self-seeker, and in searching, he ultimately found that love is the connective tissue. There’s a reason the hippies loved him. But during his turbulent lifetime, Hesse saw things that would turn many away from such sentiment, yet he still managed to not just feel love and peace, but through psychotherapy and self-discovery, to intellectually show how to go about attaining it. As such, the winner of the 1946 Nobel Prize in Literature remains the most important author in my life, even if I haven’t read one of his books since grad school. Yet when you Google “top authors of all time,” Hermann’s face doesn’t appear. And when you go to Ranker’s list of Best Writers of All Time, you have to scroll all the way down to #57 to get a glimpse of Hesse. And that’s just wrong.

Of course, you don’t win a Nobel Prize in Literature for two great books. Before going back to The All at the ripe old age of 85, Hesse delivered many more inspiring words, including the other two of his novels I’ve read, Demian and Narcissus and Goldmund, which are both revelatory and transportive stories of spirited self-discovery in the face of annihilation. But taken together, the one-two gut/mind/soul punch of Siddhartha and Steppenwolf, gracefully connecting Western culture, Jungian individuation, and Eastern Mysticism, lays a path for which the lost may follow, a trail that meanders along a well-traveled, well loved, and well-lived life, and so on into the next one.