The pit looks like a passage to the underworld. Rimmed in black rocks and ringed in ash, the tent-sized hole gapes with a certain menace. But this is not a passage to the underworld. It’s an oven.

We are at an unnamed mezcal distillery high in the mountains of Oaxaca, Mexico. The tiny distillery consists of a dirt yard, the pit, and a shed that contains an old copper still, a holding tank brimming with fermenting agave fiber, and an immense stone wheel. Beyond the enclosure, fields of spiky agave, or maguey, stretch up into the forested slopes.

This yard is one of hundreds of mom-and-pop distilleries that dot the mountains south of Oaxaca City. A far cry from the modern autoclaves of the big tequila distilleries, these operations work with fire, dirt, stone, and the age-old art of fermentation. You want artisanal booze? Try something burro-powered. Yes, the stone wheel that crushes the maguey fiber is actually pulled by a burro.

Making Mezcal (the traditional way)

Here’s the process: Men and women harvest agave from the surrounding fields and mountains. Jimadores (professional agave harvesters) cut off the spiky leaves and bury the agave hearts, or piñas, in a giant roasting pit. After roasting for about a week, the smoking agave hearts are removed from the pit and ground to fiber. Next the palanquero (distiller) settles the fiber in vats, where it will ferment for a week or two. At the end of the fermentation period, the viscous liquid is ready for distilling in a copper or clay still. Mezcal is typically distilled twice.

Tequila and Mezcal: What’s the Difference?

Mezcal is a distilled liquor made from the agave plant, a member of the botanical order asparagales, which includes asparagus and narcissus. Historically, mezcal was a blanket term for any type of agave spirits, meaning that tequila is technically a type of mezcal, albeit one made in a specific region (Jalisco and parts of four surrounding states) and from a specific type of agave, agave tequilana.

Today, tequila and mezcal are considered separate designations. Taste-wise, tequila differs from traditional mezcal because tequila distilleries employ industrial processes, replacing pit roasting with modern ovens or autoclaves. Good mezcal is smokier, earthier: these distinct flavors stem from artisanal methods: the smoke of the pit, the use of diverse species of agave (including wild plants) and, sometimes, from the clay of the traditional still. (That said, mezcal doesn’t need to be super smoky in order to be good — some quality mezcals don’t taste particularly smoky.)

Mezcal was once tequila’s wild, unregulated cousin, but these days Mexico has gotten hip to the cultural and economic value of its heritage liquors, and mezcal is now its own denomination, with its own sets of rules, regulations, and certifications. If a bottle is officially designated “mezcal artesanal” and labeled as such, it means that the spirits were made in a specific region by a specific process that may include either pit roasting or the use of masonry ovens.

Varieties of Mezcal

Like tequila, mezcal is sold “fresh” and aged. The current mezcal designations are as follows:

Blanco or Joven — unnaged.

Reposado—rested for a minimum of two months in a wooden container.

Madurado en vidrio — rested in a glass container for a minimum of twelve months. (This has a wonderful mellowing effect.)

Añejo — rested for a minimum of twelve months in a wooden container.

Abocado con — mezcal that directly incorporates additional ingredients for flavor. See fruit, herbs, flowers, honey, vegetables, or insects.

Destilado con — mezcal that’s distilled with additional ingredients, which may range from plums to the famous pechuga, or chicken breast.

Agave must mature for between four and ten years before harvest, which distinguishes agave spirits from all other forms of liquor. More than any other spirit, mezcal is influenced by the plant itself. Thus, mezcal labels often reference the type of maguey used in production. For example, tobala mezcal is made from A. potatorum, a small wild maguey that grows in the extreme highlands. While tobala is sought after, it’s not the holy grail: Tepextate mezcal costs upwards of $200 a bottle because it’s made from a wild agave so rare that a maestro mezcalero might find only five or ten plants in his lifetime.

The politics of mezcal

Mezcal was once the drink of Mexico’s working class, and derided as firewater. These days it’s the hippest thing on the menu from Mexico City to Brooklyn. Unfortunately, the boom in popularity isn’t necessarily helping the rural people who make traditional mezcal.

Many small distilleries don’t have any way to get their product to a bigger market. Big distributors will pay small distilleries a pittance for their quality mezcal, label it, and then sell it for $100 a bottle.

This year, the Mexican government issued a new labeling law: Norma Official Mexicana 177 (NOM 177). Ostensibly mezcal designations allow small producers to differentiate their product from big industrial producers. But the NOM also allows industrial nontraditional producers to label their bottles as mezcal. Mezcal made by old school methods will be labeled “mezcal artesanal” or “mezcal ancestral.” Here’s the breakdown on the new labeling standards:

Mezcal

This broad designation covers “mezcal” produced using the same industrial processes that are used by major tequila manufacturers.

- Agave hearts or juice may be cooked in autoclaves.

- Crushed by basically any method.

- Fermented in wood, concrete, or stainless steel tanks.

- Stainless steel column stills are permitted.

(This doesn’t mean that all mezcals that fall under this label are using totally modern methods. For example, a mezcal may use some traditional methods but fail to meet one requirement for the artesanal label and thus be relegated to the underclass.)

Mezcal Artesanal

- Agave hearts may be roasted in an underground stone oven or above-ground masonry oven.

- Crushed by traditional or industrial methods.

- Fermented in stone, earth, wood, clay, or animal skins. Agave fibers mandatory.

- Distilled with direct fire on a copper alembic or clay pot still. Agave fibers must be included.

Mezcal Ancestral

- Roasted in an underground stone oven.

- Crushed by hand, with a tahona, or with a Chilean or Egyptian mill.

- Fermented in stone, earth, wood, clay, or animal skins. Agave fibers mandatory.

- Distilled by direct fire on a clay pot still. Agave fibers mandatory.

What to drink?

We asked renowned mezcal expert Clayton Szczech of Experience Mezcal to weigh in on a few of our favorite brands. In choosing producers for his tastings, tours, and “mezcal camps,” Szczech considered politics as well as taste. “Right now there’s a real need for people to understand why mezcal costs what it does,” he says. “What I’m trying to do is look at these brands and figure out where more of that money is getting back to the producer.” With that in mind, he came up with four recommendations for delicious mezcal that is produced with respect for the environment and culture of rural Oaxaca.

Tosba

“This is a (rare) producer-owned brand. Mezcalero Edgar González is single-handedly reviving the mezcal tradition in his remote Zapotec village of San Cristobal Lachirioag. He’s produced espadín, tobalá and pechuga from the beginning, and many of his experimental plantings of maguey from other regions are about to mature, and all will be worth seeking out. This is one of the best mescals you will find at such an accessible price point.”

Real Minero

Real Minero

“Real Minero is a family-owned brand of delicious clay-pot distilled mezcal from Santa Catarina Minas. The distillery is run by Graciela Ángeles. She’s a unique combination of traditional (having learned mezcal from her late father) and modern (being a rural sociologist by training) and they maintain one of the most traditional processes of any mezcal you can buy in the US. As demand for wild agave grows, the survival of many species is under threat. Real Minero is doing more than perhaps any other brand to preserve and repopulate over a dozen wild varietals.”

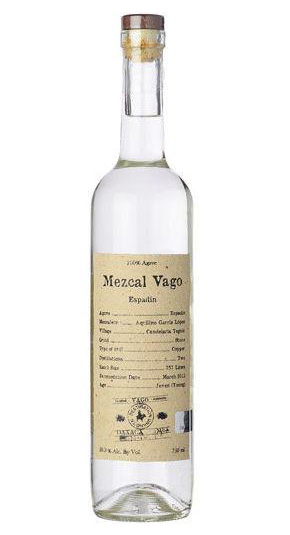

Vago

Vago

“I unabashedly recommend this as an awesome artisanal mezcal. Vago was started by Judah Kuper, a gringo surfer who fell in love with and married the daughter of an old-school, traditional mezcalero, Aquilino García, in the remote village of Yegolé. Some Vago expressions are produced by Aquilino, and the even more old-school clay-pot distilled expressions are made in Sola de Vega by “Tío Rey” Rodriguez. Vago’s labels are meticulously detailed, so you always know exactly what you are buying, down to the date it was produced.”

El Jolgorio

El Jolgorio

“This is a Oaxaca-based brand. They’ve done more than anyone to bring previously unknown magueys to the marketplace. The El Jolgorio line is mostly wild magueys.”

(Still thirsty for more? Consider planning your next trip around mezcal. See Experience Mezcal for details on tours and camps.)

Looking for a great Cognac for your next event? We have you covered on crafting a tasty Old Fashioned.