I pride myself on being the literary type. I’m a word guy, perhaps because my mom was an English teacher and I had no choice. Regardless, after having studied them for seven years, now words provide me with a living, while still feeding my soul – particularly those words found in American classics. What can I say? I’m a classic American.

“I didn’t just like the book, I loved it. It’s one of those rare novels that slowly draws you into a very peculiar point of view – in this case the great Arturo Bandini’s – until you’re so wrapped up that the sparse and essential words sweep you up in the end, and hold you aloft for the final passages, as the whole cosmic point poetically unfolds into the ephemeral bliss of higher understanding.”

I’m also a Los Angeles guy; though I’ve lived here for 15 or so years, I only just came to realize as much upon moving back from Washington. See, I grew up in Denver, and when I first moved to L.A., I got homesick for the Colorado Rockies. But when I moved to Washington, I got homesick for Playa del Rey, my gritty little beach town within Los Angeles County, where I am now happily planted. And it finally feels like home.

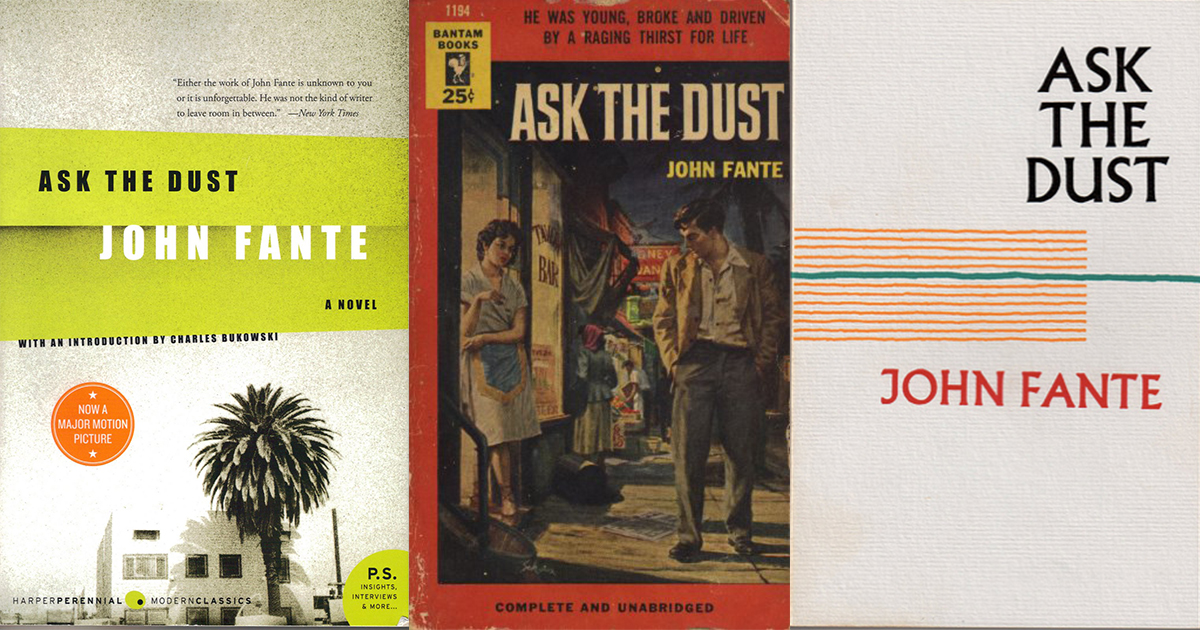

With such a legacy, it’s no wonder why I’m embarrassed to admit that I had never heard of John Fante, a celebrated American writer who grew up in Denver, and went on to become the quintessential L.A. novelist, before Charles Bukowski could make such a claim. In fact, when Bukowski discovered Fante at the L.A. Public Library, it was like finding “gold in the city dump,” as he writes in the introduction of Harper Perennial ‘s Modern Classics edition of Ask the Dust. Bukowski was so taken with Fante’s poetic yet real style that Fante became his main literary influence. Yet I had still not heard of such a legend as Fante until a few weeks ago, when, just because he thought I’d like it, my friend Russell with the biggest smile on the beach, handed me a copy of Ask the Dust — a short, perfect novel widely regarded as an American classic, and one so popular as to have inspired a Hollywood version starring Colin Farrell and Salma Hayek.

I don’t know what part of me gives off the Fante feels, except that I love words and one of the book’s main characters is named Camilla, which also happens to be my wife’s name. Regardless, Russell was dead on, except that I didn’t just like the book, I loved it. It’s one of those rare novels that slowly draws you into a very peculiar point of view – in this case the great Arturo Bandini’s – until you’re so wrapped up that the sparse and essential words sweep you up in the end, and hold you aloft for the final passages, as the whole cosmic point poetically unfolds into the ephemeral bliss of higher understanding. That is the power of Fante’s words, written in 1939 about life in Depression-era L.A., and they still resonate across the skyscrapers of downtown.

At base value, the book is about a young Italian-American, Bandini, who left his family in Colorado to become a writer in L.A. We basically move in with him, into his tiny rented motel room, with his outlandish neighbors, none of whom ever seem to have any money, least of all Arturo. And then we meet Camilla, the exotic waitress at the corner bar, and Arturo is forever ruined. Though a mere synopsis can’t do it justice, one written by the author himself certainly lends some poetry to the effort. From the same edition, before having completed Ask the Dust, here’s what Fante told his editor about what to expect:

“New book will be called ‘Ask the Dust on the Road,’ and the story is in a Los Angeles background (no Hollywood stuff). Story of a girl I once loved who loved someone else, who in turn despised her. Strange story of a beautiful Mexican girl who somehow didn’t fit into modern life, took marijuana, lost her mind, and…”

Sorry, the last part there is a bit of a spoiler, and I wouldn’t want to ruin one of the truly great endings in literature, even at the expense of butchering the esteemed author’s own words. And you know how I feel about words. In the end, they’re what I love most about Arturo, and possibly Fante himself; indeed, starving Arturo’s belief in his words never waver. And regardless of the insanity of his unnatural world-order crumbling around him, he knows, deep inside, that his own words will save him.