Jesse Capen spent ten years trying to solve the mystery of the Lost Dutchman Mine. Although Capen worked the graveyard shift as a bellhop at the Denver Sheraton, his study of the legendary Arizona mine was a full-time obsession. And why not? The story has it all: Spanish gold, wiley priests, an ancient Apache curse, murder, a massacre, cryptic maps, riddles, dramatic deathbed proclamations, and, of course, buried treasure.

In late November of 2009, Capen, 35, decided it was high time he acted on his dream of finding the treasure that’s rumored to be hidden in Arizona’s aptly named Superstition Wilderness Area. He drove south from Denver, planning to spend a month exploring the mountains east of Phoenix. After setting up camp, he climbed to the 4,892-foot pinnacle of Tortilla Mountain and left a note in a metal canister: “Jesse Capen was here. Dec 4, 2009.” It was his last message to the world.

Designated in 1939, the Superstition Wilderness Area now encompasses 160,200 acres of craggy desert. The dry land is crisscrossed with trails, but much of the region is impassible. The rough and steep nature of the terrain allows treasure hunters to dream that the “Dutchman’s” legendary gold is lodged away in some apparently inaccessible crevice–despite the tens of thousands of people who have searched for it.

The legends of treasure are numerous and exceedingly intricate. In one version, the treasure is a cache of gold and silver crosses, candelabras, and chalices that dates back to 1764, when the Spanish crown is expelling the Jesuits from the Americas. Feeling vindictive about getting kicked out of their missions, the Jesuits gather the valuables from the churches in New Spain’s vast northern territories. Instead of handing these sacred treasures over to the enemy king, they take a mule train to the Superstition Mountains where they hide the loot in a cave near a rock spire.

The next legend is slightly more plausible. In 1840 an aristocratic Mexican family named Peralta develops rich gold mines in the Superstition Mountains. Their activities anger a band of Apaches, who warn the Peraltas to stay out of their sacred lands or face the wrath of the God of Thunder. The Peralta party ignores the Apache threat. The Apaches are pissed and send riders to gather a larger force. When the Peralta party packs up to transport their gold back home to Sonora, the Apache warriors ambush and massacre the Mexicans. The warriors then bury the gold and hide the entrance to the mine. (You can read a detailed version of this legend here.)

Years later, a man called Dr. Thorne supposedly befriends the same Apaches. After he cures a sick chieftain, the tribe rewards him by leading him, blindfolded, to a gold mine. They invite him to take as much gold as he can carry away.

None of these stories have been convincingly verified.

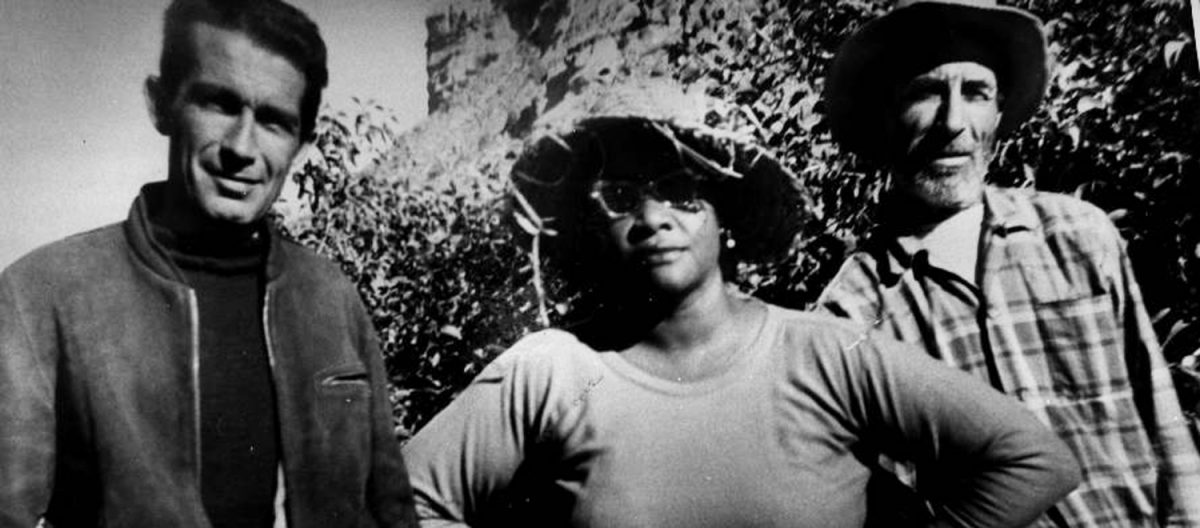

Things get a bit more concrete in 1863 when the famous “Dutchman” enters the story. The man in question was actually a German immigrant named Jacob Waltz, who arrived in the United States around 1839 and was lured west by the California gold rush. He prospected in California but never struck it rich, and headed to Arizona in 1863. He was one of the first pioneer prospectors in Arizona’s Bradshaw Mountains and eventually filed a homestead claim on the banks of the Salt River. Although he farmed the land, he continued hunting for gold in the mountains. He died in Phoenix in 1891, in the care of his friend Julia Thomas, an African American baker.

That’s all verifiable. But from here the story descends into a snarl of speculation. One-hundred-and-thirty years of speculation, in fact. According to most versions of the story, Waltz was a salty white-whiskered codger who would travel into the Superstition Mountains each year and return to town with gold nuggets of unusually high quality. These he would spend on drinking binges.

In one version of the story, Waltz has a prospecting partner named Weisman. Weisman winds up dead and Waltz claims the man was murdered by the ubiquitous Apaches, but locals speculate that Waltz murdered Weisman to protect the secret location of the lost Peralta mine or a hidden cache of Apache gold. Waltz refuses to answer any questions. Many people attempt to tail him into the wilderness, but the wily old bastard evades them all.

Back to the facts: In 1891, Waltz fell ill, likely from pneumonia. On his deathbed, he told Julia Thomas the location of the gold, but his directions were cryptic. Thomas became the first of hundreds of people who would squander their lives hunting for the treasure.

As I mentioned, the story has many versions, and the entire cast of characters is huge — with Waltz’s various friends and neighbors (and their descendants) feuding over maps and clues and the cache of gold that Waltz supposedly stashed under his bed before he died. Then come more recent developments, like the mysterious and probably phony Peralta stone tablets, which supposedly hold the key to the mystery. I’m not qualified to tell that convoluted tale. If you’re interested, you’ll need to look to the folks who’ve devoted lifetimes of study and speculation to the case.

Which brings me to my point. What really interests me is not so much the legend itself — but rather its eternal allure. Three years after bellhop Jesse Capen set out on his treasure hunt, his skeleton was found in a crevice in the Superstition Mountains. But Capen was not the lone victim. Scores of people have died or been murdered while hunting for Waltz’s treasure.

Adolph Ruth is one of the most famous victims. Like Waltz, Ruth was a German immigrant who had gold fever. Unlike Waltz, Ruth was an elderly veterinarian and ill-suited for roughing it. He was 78 when he set off into the mountains with an old map that was purported to show the Peralta mine. In June of 1931, Ruth set up camp in West Boulder Canyon, near Willow Springs. He never returned to civilization. Six months later his skull was discovered in a ravine. Although it seems likely that Ruth died of natural causes, his disappearance spawned the pervasive conspiracy theory that he was murdered for the map. This story was picked up be periodicals and, ironically, helped popularize the legend of the mine.

After that they came in hoards. The obsession with the treasure spawned several formal societies of “Dutch hunters,” including the famous Dons of Arizona, which formed in 1931 and began hosting annual treasure hunts–replete with barbecues and pageants and guests costumed like Spanish aristocrats. Dons of Arizona membership rolls include Barry Goldwater and Harry S. Truman.

But Dutch hunting wasn’t all fun and games. In 1956 a feud erupted between two camps of prospectors who had claims near the stone spire known as Weaver’s Needle. According to Dutchman scholar Tom Kollenborn, the feud began when prospector Ed Piper arrived on the scene and began squabbling with Celeste Maria Arva Jones, an opera singer from Los Angeles who claimed to have divine visions that had led her on a hunt for the Jesuit treasure. She’d staked her claim six years before Piper’s arrival, had the habit of carrying a sawed-off shotgun, and was not to be trifled with. She allegedly hired a man named Robert St. Marie to settle things with Ed Piper.

Piper instead shot and killed St. Marie, but claimed that St. Marie had attacked him. Piper successfully plead self-defense, and returned to the mountains, where he continued battling with Jones. Eventually the Forest Service got exasperated and kicked everyone out. At that point, Jones disappears from the historical record.

Murders aside, the accidental death toll has been fairly steady since the beginning. Historian Tom Kollenborn estimates that between 50 and 70 people died in the the Superstition Wilderness during the 20th Century. The 21st Century has seen a slight uptick, with an average of about one death a year. Naturally there’s speculation about an ancient Apache curse, but the real cause is probably a tad more mundane. The terrain is notoriously rough and hot. Many of the missing hunters went into the desert alone and under-prepared. A significant number were elderly or out of shape.

Less explicable is the level of obsession. Death seems to feed it. In addition to the legends of treasure, there are now legends and conspiracy theories that spiral from the lives and deaths of countless treasure hunters. One-hundred-and-thirty years after Waltz’s deathbed proclamation, Dutch hunter forums hum with activity. Dutch hunters trade maps and clues. Dutch hunters hold reunions in the Superstition Mountains, where they spin conspiracy theories and argue about the exact dimensions of the floor plan of Julia Thomas’s bakery.

Is greed a factor? Of course. Who hasn’t dreamed of striking it rich? But there’s obviously more to it. The treasure of the Lost Dutchman Mine speaks to the heart that won’t surrender to the mundane. This obsession is so very American: born of a romantic belief in the adventure as redemption, fueled by childhood daydreams that refuse to die, kept alive by the same delusional optimism that spurred westward expansion and forged the country we know today — hidden gold and all.