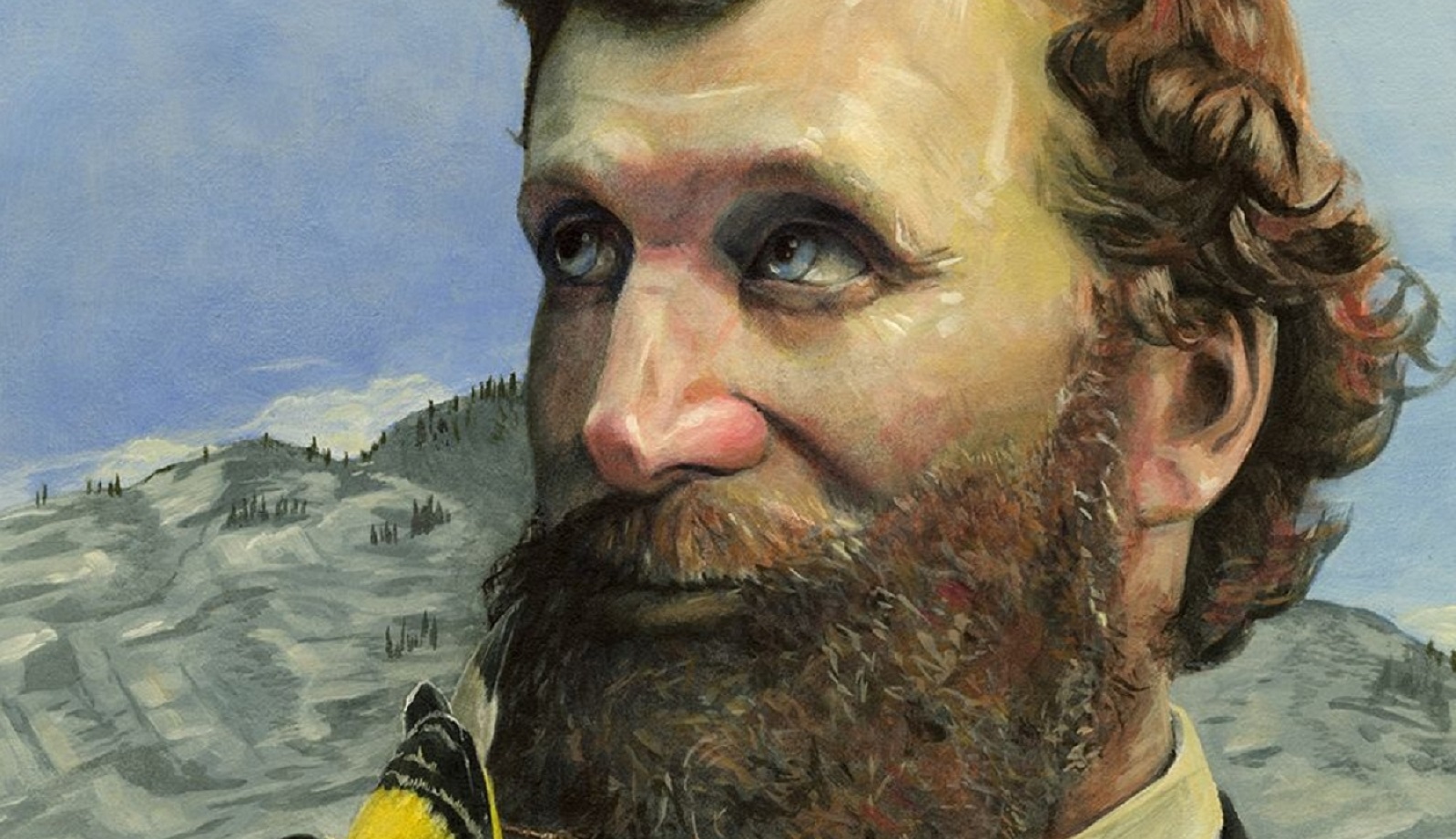

John Muir was a man back when being a man required having balls.

Temporarily blinded in a factory accident in 1867 when an awl pierced his eye, upon recovery decided to walk from Indiana to Florida before sailing to San Francisco where he continued his journey on foot by hiking to the Sierra Nevada mountains. He climbed a 100-foot tall Douglas spruce during a colossal wind storm, handed President Theodore Roosevelt a deprecating letter, and advocated for the creation and protection of no less than five national parks. He was John of the Mountain, and his incredible connection to the outdoors was as much talk as action. Muir helped found and was the first president of the Sierra Club, and he did his part to convince Theodore Roosevelt to protect vast swaths of natural beauty, and he delved headfirst into wilderness adventurers in an effort to understand the world and his place in it. He did these things armed with a walking stick and a visceral comprehension of man in the outdoors.

The world is a different place than it was during the 19th-century, but we can learn something from men like Muir that will make us better having learned it.

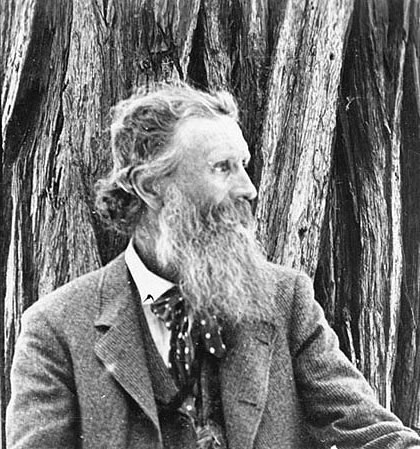

Muir and the Sierra Club

Muir helped found the Sierra Club in 1892. He held the office of first elected president until his death in 1914. The official mission statement of the Sierra Club is “To explore, enjoy, and protect the planet”, but Muir said that he wanted to form the organization to “make the mountains glad”. Scores of men have tried to establish themselves as major makers in history, to have their names remembered for the ages. John Muir could care less if his name was remembered because he only wanted his beloved mountains and trees protected, and made available to the world to experience as he so lovingly did.

He did not achieve this feat by barking and yelling, pounding his chest in defiance to the rest of the world around him. Muir accomplished this feat relatively quietly and with the help of friends and sympathetic interests. He did it for what he loved and not for himself.

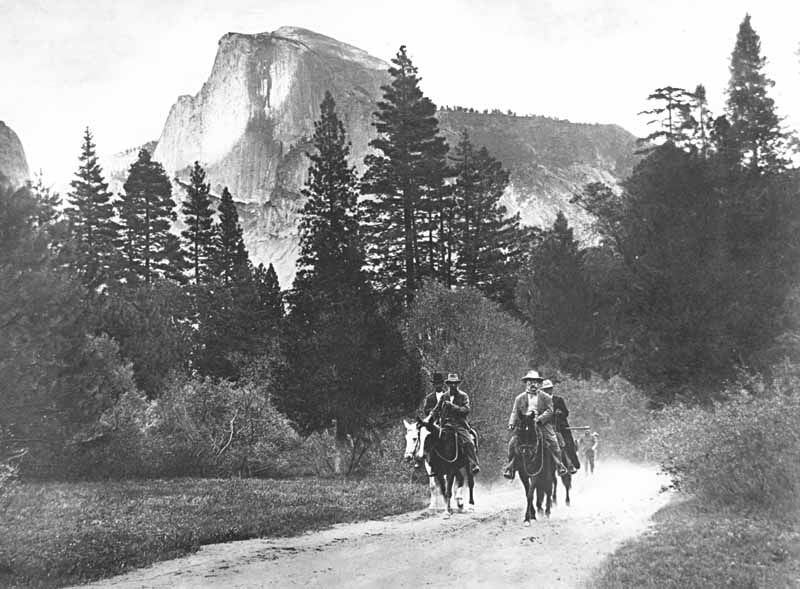

Muir, Meet Roosevelt

In 1903 Muir went on what came to be known historically as a famous camping trip with Theodore Roosevelt. The 3-day trip in Yosemite presented an opportunity for Muir “to do some forest good in talking freely around the campfire.” Muir spoke to the president about the importance of federally protecting these great forests. Known for his appreciation of forthrightness, Roosevelt took Muir’s unadorned words to heart. Theodore Roosevelt would eventually work to protect five national parks, 18 national monuments, 55 national bird sanctuaries and wildlife refuges, and 150 national forests over the course of his presidency. This decision was largely influenced by Muir.

Muir spoke to Roosevelt directly, without pomp or guile. The modern world is full of sideways talk and coercive jabbering, forgoing the honesty of straight talk in favor of appeasement. Muir did not mince words, and his directness is a quality we could all make use of.

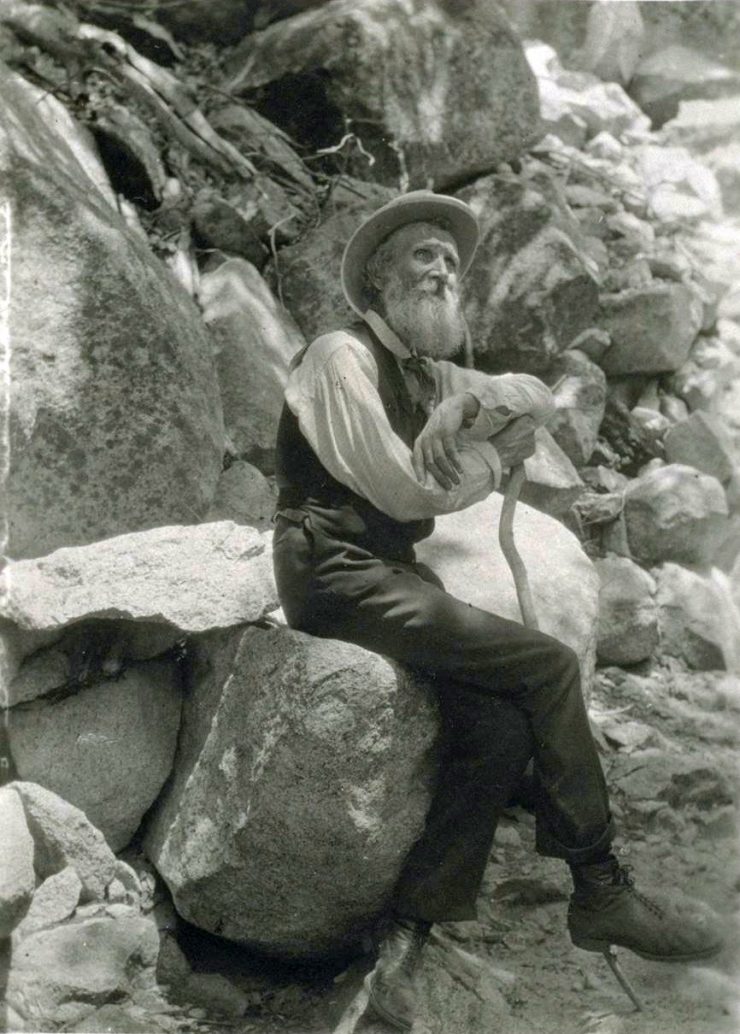

John of the Mountain

The most important takeaway about John Muir is that the man loved the wilderness with a type of ardor we should all strive to understand. His journals describe his reflections on the natural world and man’s place in it. Time in the outdoors defined his existence, and because he knew this existential truth he could understand his own being with rare clarity. The best example for this is his ascent of the 100-foot Douglas spruce. Muir was camping in the forest and witnessed a terrific storm brewing. Ever the adventurer, he decided to climb the tallest Douglas in a grove of trees; at the top of the tree he felt the timber sway back and forth, bending at 30-degree angles but never cracking. He closed his eyes to feel entirely alone during this experience, and at other times opened them to watch the sea of trees blow like blades of grass under titanic winds.

When he returned to his campsite, after the storm abated, he wrote in his journal,

“We all travel the milky way together, trees and men…

…When the storm began to abate, I dismounted and sauntered down through the calming woods. The storm-tones died away, and, turning toward the east, I beheld the countless hosts of the forests hushed and tranquil, towering above one another on the slopes of the hills like a devout audience. The setting sun filled them with amber light, and seemed to say, while they listened, ‘My peace I give unto you.’

As I gazed on the impressive scene, all the so called ruin of the storm was forgotten, and never before did these noble woods appear so fresh, so joyous, so immortal.”

Muir possessed an understanding that the worst of times were only a forerunner to better, more peaceful ones. It’s a rare ability to have this vision, but it’s an incredible one to cultivate. Muir stepped into the storm, climbed a terrific height to experience it in its fullness, and after weathering the wind and rain found solace in the entire experience. This is an incredible awareness of the moment, of life and all it has to offer.

The mountains are calling and I must go…

Muir was a man back when being a man required truth, honesty, and self-awareness.

The more time spent in the outdoors listening to the wind in the trees and the churning rivers the better. It’s where we all come from, and man cannot find true solace away from the wild places of the world.

Ultimately, Muir represents an ideal example of a man. He loved fiercely and felt an irresistible compulsion to defend and protect his interests. He spoke directly and plainly, and was unafraid to open his heart to the beauty that surrounded him. You don’t need to be a woodsman to appreciate that.

As a final note, check out M. Richard’s article Road Tripping California’s Remote Highway 395 here on Factory24, and look for that special nod to Muir’s beloved Yosemite Valley.