Millennia of tradition can make French wine seem daunting. Why bother with Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée and Cru when you can just drink a nice California Cabernet Sauvignon? Well, when it comes to impressing the ladies or your clients, it’s useful to know your Bordeaux from your Beaujolais. Plus, delicious.

Bordeaux is the most famous and prestigious French wine region, partly due to its long history and early international reach. In the twelfth century, the merchants of Bordeaux began shipping barrels of wine down the Gironde Estuary and onto ships bound for England and Scotland. A few hundred years later, the Dutch would become so obsessed with Bordeaux that their engineers would drain the region’s swamps in order to facilitate transport of wine barrels. (Handily, this also freed up more land for cultivation.)

The Land

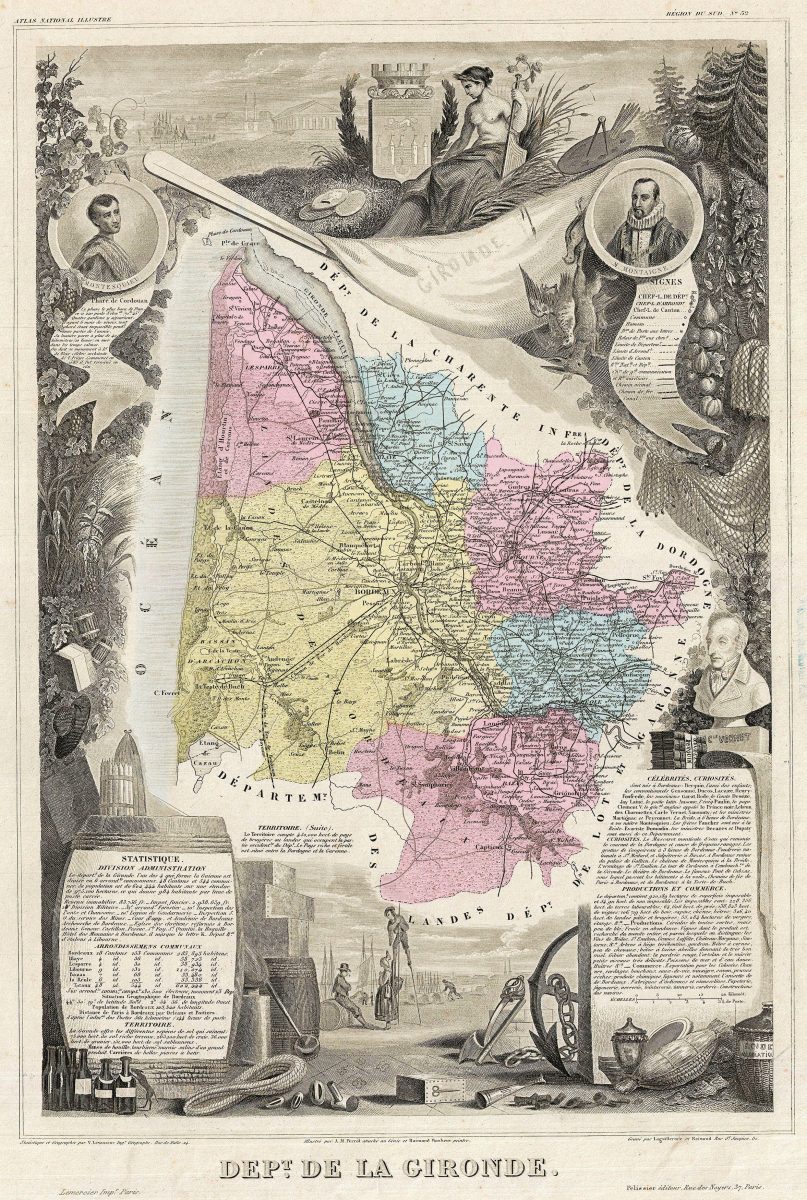

Bordeaux is the largest wine region in France and, at 290,350 acres, one of the largest fine wine regions in the world. (It’s six times larger than the Napa Valley.) Low rolling hills create distinct variations in sun exposure, drainage, and soil quality. The most famous vineyards are on the land with the best drainage, such as the gravel of the Medoc and Graves, and the calcerous terrain of St-Emilion.

The climate benefits from an abundance of rivers and streams, proximity to the Atlantic Ocean, and the storm break provided by the immense pine forests of Les Landes. In the maritime climate that washes inland with the Gironde estuary, danger from severe frost is rare.

The Grapes

Bordeaux wine, is, of course, named after a region, not a grape. Both red and white Bordeaux are made by blending grape varieties. The region produces very good white wines, but red wines dominate.

In order to call a red wine Bordeaux, it must be made from one or more of six types of red grape (Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, Petit Verdot, Carmenere, and Malbec). The big two are Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon, grapes high in the tannin that gives red Bordeaux its famous structure.

Seven varietals may be used in white Bordeaux, but the grapes to remember are Sauvignon Blanc, Sémillon, and Muscadelle. Sémillon is the leader of the pack and is the source of the creamy texture and honeyed notes that characterize many of the region’s fanciest whites.

Regions

Of the wine produced in Bordeaux, about 40% of red and 70% of white is labeled simply as Bordeaux. More prestigious wines are labeled by specific geographic designations. These appellations are strictly controlled.

Bordeaux has a dizzying quantity of sub-regions, and each sub-region is divided into smaller appellations, which are typically named by village. Books the size of ottomans have been written about the distinguishing characteristics of the various sub-regions, communes, vineyards, and chateaux. In other words, it’s far too complicated to cover here, so we’ll stick with the two most famous major areas: the Left Bank and the Right Bank.

Left Bank

The west bank of the Gironde estuary and Garonne river is home to the world’s most august vineyards. In fact, the Left Bank boasts all of the wines from the prestigious classification of 1855. Cabernet Sauvignon dominates this side of the river. Left Bank wines are known for their impressive shelf life, and the region’s finest wines are best aged at least ten years. The major appellations are Margaux, St. Julien, Pauillac, St. Estephe, Haut Medoc, and Pessac Leognan.

Right Bank

Merlot and Cabernet Franc dominate. Right Bank vineyards tend to be smaller and less grand, but admired for recent innovations in winemaking. Right Bank wines are known for richness, ripeness, and concentration. Saint-Émilion and Pomerol are esteemed Right Bank appellations.

Classifications

In addition to region and sub-region, French wine labels may also include classifications, or quality rankings. The most famous of these is the Classification of 1855. If you’re thinking “Aha! Excellent. A simple way to ascertain which wines to buy,” then think again. If you’re someone of average income, the only thing the Classification of 1855 will tell you is which wines you definitely can’t afford. Let me explain…

In preparation for a wine exhibit at the Universal Exposition in Paris (a world’s fair), an organization of wine merchants came up with a ranking system for the wines of Bordeaux. The red wines they deemed worthy of ranking all came from the Médoc region, with one exception: Château Haut-Brion in Graves. The fanciest chateaux were classified as Premier Cru (First Growth), followed by second growth, third growth, fourth growth and fifth growth. The system was relatively simple: The rankings were based on the price each wine could fetch on the market.

If fifth place doesn’t sound too prestigious to you, think again. The snobby wine merchants only bothered to classify the fanciest wines and totally ignored the hundreds of châteaux that made affordable wines. So a Cinquiemes Cru (fifth growth) wine still has prestige, and may cost hundreds of dollars per bottle.

So it’s a classification that at least works for rich people? Actually, not even. The classification has only been updated once since 1855 (when Baron Philippe de Rothschild successfully lobbied to get Ch Mouton-Rothschild promoted to first growth), and there’s some argument that the ranking is no longer totally accurate. You can bet that a wine labeled Premier Cru is going to be excellent, but some fifth growth wines now rival the quality of second growth wines, and some second growth wines (called Super Seconds) are arguably as good as first growth wines.

If you find this depressing, wait. There’s more. The Médoc classification of 1855 only covers a small fraction of Bordeaux. There’s also the 1855 classification of Sauternes and Barsac, the 1953 classification of Graves (revised in 1959), and the 1954 classification of Saint-Émilion (intelligently mandated to be revised frequently). All of these classifications use slightly different language, so Premier Cru doesn’t mean the same thing Saint-Émilion as it does in the Médoc. But there’s one small spark of light for the aspiring oenophile: You can thank the good people of Pomerol, who never classified their wine. Á votre santé!